|

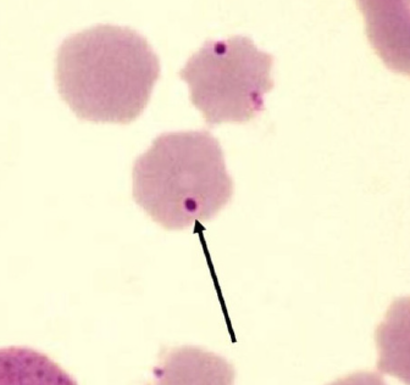

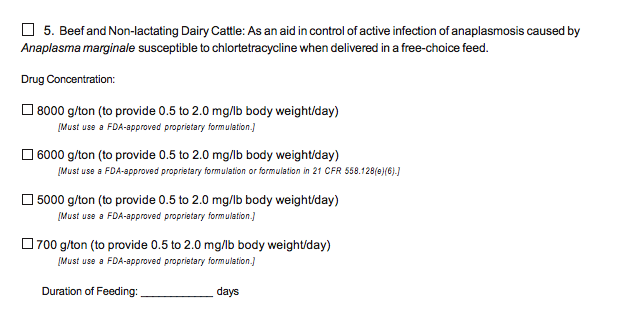

Dr. Michelle Arnold, University of Kentucky Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory What is Anaplasmosis? Anaplasmosis is a disease caused by Anaplasma marginale, an organism that invades cattle red blood cells (Figure 1) and causes severe anemia, often resulting in death. In Kentucky, the disease affects adult cattle in the fall of the year with nearly all cases occurring from late September through the first 1-2 weeks of November. What are the symptoms of anaplasmosis? This organism causes anemia in adult cattle which means there is an abnormally low number of red blood cells circulating in the bloodstream. Lack of red blood cells results in oxygen deprivation to the vital organs but clinical signs are not noted until 40-50% of red blood cells are destroyed. Infected cattle will show signs of weakness, lagging behind the herd, staggering, rapid breathing and sometimes foaming from the mouth. Affected cattle quit eating and tend to rapidly lose weight. Most become very aggressive due to lack of oxygen to the brain. Mucous membranes will appear pale early in the course of disease and progressively turn yellow in color due to jaundice. Death can be sudden, especially with exercise, or cattle may be found dead with no prior symptoms. Typically, several adult animals in a herd will die within a short (1-2 week) span of time. Do all cattle with anaplasmosis show these same symptoms of disease? No. Younger cattle, especially less than 6 months old, rarely exhibit signs of disease due to rapid and active production of new red blood cells (RBCs) in growing calves. Anaplasmosis in animals from 6 months to 2 years of age may be misdiagnosed as pneumonia because symptoms of both conditions include fever and increased respiratory rate. Older animals (> 2 years old and up) are at elevated risk for disease and death but some are able to mount an effective immune response without obvious signs of sickness. How do you treat an animal showing signs of Anaplasmosis? Treatment with tetracycline is essential for survival if showing signs of disease. No injectable antibiotic is formally approved for treatment so any form is “extra label” and must be given under veterinary direction. A single intramuscular injection of long-acting oxytetracycline at 22 mg/kg of body weight (BW) or 10 mg/lb BW in the muscle will often stop the progression of anemia by slowing replication of the Anaplasma organism, allowing the immune system to take over and save the animal. However, be aware that severely affected cattle may die due to stress when walked to the barn or going through the working chute. In an outbreak situation, it is recommended to treat all adult cattle in the herd with injectable oxytetracycline (for example, LA-200®, LA-300®), then begin feeding chlortetracycline (CTC) at the control dose (0.5-2 mg CTC/lb BW/head/day) in medicated mineral or feed throughout the rest of the vector (fly) season. Medicated mineral may be offered free-choice assuming mineral consumption is consistent among the herd. Alternatively, hand feeding Aureomycin® daily in feed to deliver 0.5 mg/ lb BW/head/day will also control active infection. If an animal survives the initial infection, then what? Will they get it again? If an animal (regardless of age) becomes infected with Anaplasma marginale and survives, that animal will become a “carrier” of the organism for life. As carriers, they are never sick due to Anaplasmosis again but serve as reservoirs of infection for other, naïve animals. Infected bulls that survive may be infertile for up to a year while pregnant cows that survive almost always abort during recovery from infection. Recovery takes at least 2-3 months to rebuild red blood cells and regain lost weight. How is Anaplasmosis spread? Anaplasmosis is considered a “tick-borne” disease because they can spread the organism through feeding on cattle. Although ticks are important for this organism to survive and spread, transmission can be by any method that moves affected red blood cells from infected to susceptible cattle. In addition to ticks, the Anaplasma organism may be spread by biting insects (mosquitoes, horse flies, stable flies) and/or using blood-contaminated tools such as dehorners, ear taggers, castration tools, and implant guns without disinfection between animals. Probably the most common way it is transmitted is using the same hypodermic needle on multiple animals when administering vaccines to the herd. Once infected, there is a 4-8 week long incubation period before the animal develops signs of a problem. Transmission may also be from cow to calf while pregnant. How is Anaplasmosis diagnosed? If an animal is found dead and no more than 24 hours (12 hours preferred) has passed since the time of death, the animal can be submitted to a veterinary diagnostic laboratory for necropsy or a veterinarian may perform a field necropsy to determine the cause of death. If an animal is alive and showing signs consistent with anaplasmosis, the UKVDL recommends a blood sample (both a red and a purple top tube) be submitted for an accurate diagnosis. Whole blood (purple top tube) is needed for a complete blood count (CBC) with differential in order to assess the degree of anemia and to possibly identify the organism in the red blood cells. The red top tube of blood is needed for a serum test (the Anaplasmosis cELISA) to detect antibodies indicating infection and/or carrier status. However, the serum test may be negative early in the disease process. Blood should be collected and transported to the lab as soon as possible (overnight ship with cold packs). Please visit the UKVDL web site for additional information at http://www.vdl.uky.edu Is an effective vaccine available? Kentucky is among the list of states approved by the USDA for sale of the anaplasmosis vaccine marketed by University Products LLC of Baton Rouge, LA. Vaccination should keep animals from experiencing sickness and death but does not prevent infection and still allows development of the carrier state. The vaccine can be used during an outbreak and has been used in cows in all stages of pregnancy with no problems being reported. The recommendation is a two-dose regimen given 4 weeks apart with annual re-vaccination required. Immunity should develop within 7-10 days of the 2nd dose according to the manufacturer. Vaccination should ideally begin with yearlings. Bear in mind the vaccine does not prevent infection, it controls clinical disease. Again, vaccinated animals may still become infected and become carriers but should not get sick and/or die. More information may be found at: http://www.anaplasmosis.com/home.htm What is the best way to prevent problems due to Anaplasmosis? Preventing infection with Anaplasma marginale is actually very difficult due to the large number of infected herds throughout the state and the ease with which it is transmitted. In addition, antibiotics do not clear the infection and the vaccine still allows infection to occur. For these reasons, the goal is to prevent clinical disease and production losses when the herd is exposed to the Anaplasma organism and as it spreads within the herd. One effective means of control begins in the spring by feeding chlortetracycline (CTC) at the control dose of 0.5 mg-2mg/lb BW per head per day to beef cattle over 700 pounds throughout the vector (fly) season to the herd. Recent research has found it is equally effective to pulse feed CTC (offer CTC for 30 days, take a 30-day break then offer CTC for the next 30 days and so on) as offer CTC continuously for control of the disease. Many producers find it easiest to use CTC in free choice mineral rather than hand feeding CTC daily with Aureomycin®. However, with the advent of the Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD), what once was a quick trip to the feed supply store has become a far more complicated process to get medicated mineral or feed. In order to obtain CTC, a producer must have a written VFD from a licensed veterinarian to present to the feed store before purchase of the product. FDA states that “once a veterinarian has determined that anaplasmosis infection exists within a herd, whether or not clinical signs are apparent yet, he/she may write a VFD to direct the use of CTC for controlling the progression of the disease in that herd.” FDA leaves how to make this determination to the discretion of the veterinarian. How long to use the product is also left to the veterinarian’s discretion, based on his or her assessment of the disease risk. A VFD order can be issued for a maximum of 180-day duration of feeding; if needed for a longer period of time, a new VFD order must be written. On the actual VFD form for CTC, the veterinarian can only choose the #5 option (see example in Figure 2) for a free choice product. The FDA has approved several formulations for the use of CTC in free choice medicated minerals for anaplasmosis control that are effective if consumed consistently. Remember, feeding CTC is worthless if the animals are not consuming sufficient amounts so intake should be monitored. Even when feeding CTC throughout the vector season, some individual animals may still become infected and die if they do not eat enough. Using CTC or any feed additive in a manner not stated on the label is illegal and strictly prohibited for producers, veterinarians, and nutritionists. If unable to obtain a VFD or feeding CTC is not an option, vaccination is another possible control measure available that can work but is a bit pricey at $8-10 per dose. To reduce the cost, if willing to draw blood and submit for anaplasmosis testing, the vaccine can then be targeted for use in only the individuals who test negative for antibodies. Animals that test positive will not need vaccination nor CTC therapy. This Anaplasmosis cELISA blood test can be run on the same blood sample used for pregnancy testing, too.

Will Anaplasmosis always be a problem for KY cattle herds? No, the disease will finally reach a point of “endemic stability”, meaning nearly all of the animals in herds have been exposed to the disease and are immune to its effects. However, new additions to the herd purchased from areas of the US without anaplasmosis and brought to KY will be at higher risk of disease and should be tested to determine if they have been previously exposed or are completely naïve and treated appropriately. Similarly, carriers may inadvertently be cleared of the organism with a consistent, high dose of tetracycline over a prolonged period of time (a technique known as “chemosterilization”) but cleared carriers are completely susceptible to re-infection and sickness/death in subsequent seasons. Attempting to clear the organism or eradicate the disease is usually limited to high value seedstock that require international movement. Consult your veterinarian for further information about testing and disease control recommendations for your area. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

Welcome |

CONTACT US |

EMAIL SIGN UP |

|

Eden Shale Farm

245 Eden Shale Rd. Office: (859) 278-0899 Owenton, KY 40359 Fax: (859) 260-2060 © 2021 Kentucky Beef Network, LLC.. All rights reserved.

|

Receive our blog updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed